'Mountain Water (shanshui): Walking the Annapurna Track'

It is with great pleasure that I announce that this new work will be showcased at the Pingyao International Photography Festival in September this year.

'Mountain Water (shanshui): Walking the Annapurna Track'

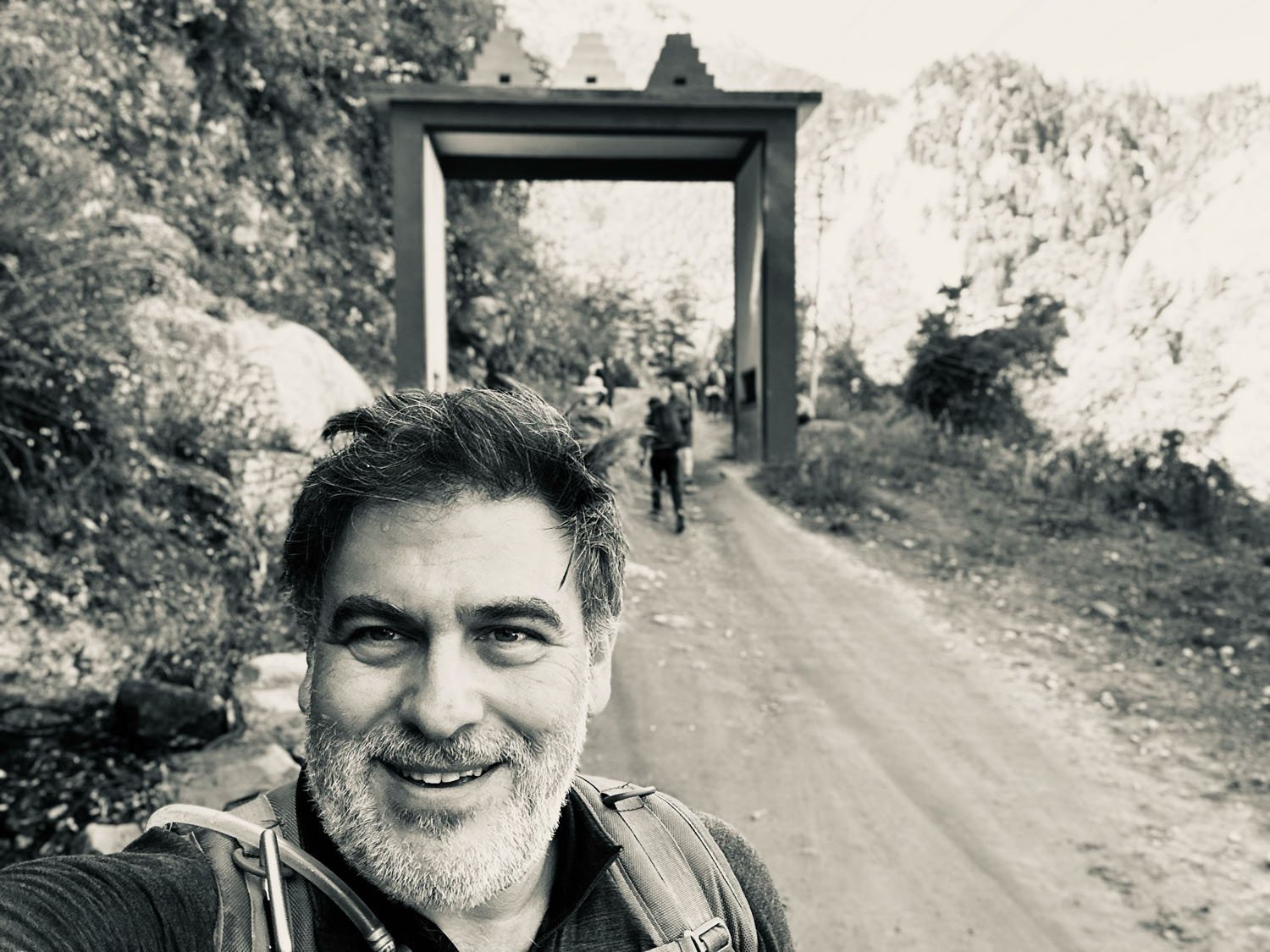

In a world where the pace of life seems to accelerate endlessly and our connection to nature often feels fleeting, my journey as an artist and photographer has led me to a pursuit that, for me and hopefully my audience, transcends this. Through my lens, I find myself irresistibly drawn to capturing the profound essence of our surroundings. My recent series of landscapes was created during a rigorous hiking expedition along the Annapurna Track in Nepal. This journey is not a documentation of physical landscapes, but a philosophical exploration of the interplay between modern techniques and the timeless resonance of artistic expression and a manifestation of the physicality of the endeavour.

The Annapurna Track, etched by the footsteps of explorers and trekkers, became the canvas for this series. I sought to do more than capture mere visuals. Rather, I aspired to bridge the gap between observer and artist, to engage with the landscapes in a manner that transcends conventions of landscape photography. My approach is a fusion of contemporary techniques and the timeless traditions based on an immersive physical connection to the making process. It’s a journey that invites us to question the boundaries that separate us from the landscapes we traverse and attempt to become part of.

Central to this exploration is the concept of "shanshui" painting, an artistic tradition exemplified in Anhui Province, China. This philosophy doesn't merely depict landscapes; it encapsulates the very essence of nature's beauty, stirring emotions, memories, and sensory experiences that extend beyond the visual. This tradition serves as a cultural and philosophical backdrop against which my photographic approach is juxtaposed, accentuating the resonances and shared elements between the two artistic undertakings.

In the upcoming sections, we will delve into the intricate interplay of my photographic techniques and the ideals of "shanshui" painting. We will explore how I blur the boundaries between photography and painting, using modern tools to infuse my images with the emotive power of traditional brushwork. Additionally, we will delve into the layering process that defines my photographic style, drawing parallels with the nuanced layering of brushstrokes in "shanshui" painting. This technique adds a dimension to my work, inviting viewers to not only see but also, hopefully feel and experience the landscapes I capture.

Moreover, we will explore how my photographs echo the pursuit of the sublime in nature, akin to the aspirations of Anhui painters who sought to encapsulate the essence and spirit of landscapes. By allowing time to operate dynamically within my images, I align with the temporal and dynamic elements inherent in traditional painting. My emphasis on the physical connection to nature and landscape, intertwined with my emotional connection to nature, mirrors the emotional bond that "shanshui" painters aimed to forge with their subjects.

My photographic journey serves as a bridge between contemporary techniques and age-old principles. Through this dialogue, I hope to emphasise the enduring relevance of blending modern tools with traditional ideals, fostering a deeper understanding of the interplay between humans and the natural world. Ultimately, this analysis urges a reconnection with nature on a profound level, echoing across time and cultures – an endeavour that lies at the heart of both my work and traditional painting.

My intent is not solely to capture the tangible world but to weave a narrative that encompasses both the visual and the emotional. This approach aligns with the ethos of the Anhui painters, who ventured into nature to capture not just the physical appearance but the essence of landscapes. My hand-held devices become modern-day brushes, enabling me to delve beyond the surface and to evoke emotions through visual storytelling.

In mirroring the immersive practice of Anhui painters, I use my hand-held devices as extensions of my senses, it sees what I feel. The importance of the physical response to hiking in this tough terrain is crucial and captured by the device. Just as these traditional artists immersed themselves in their surroundings, I too find myself immersed in the landscape, in the moment, capturing its subtleties and my physical response in real-time impressions. This shared immersion speaks to a profound connection with nature, where the act of capturing becomes a means of communion. Just as Anhui painters aimed to convey their emotional responses to nature, my use of technology becomes a conduit for translating my personal engagement with the environment.

The method behind my photographic process draws inspiration from several areas, initially I was drawn to questioning the i-devices (iPhone) ability to connect us with nature in a more immersive and deep way, rather than the ‘distractor’ it is often attributed to being. In earlier bodies of work, I quickly established when embraced as a way of seeing as much as recording it transformed from a mere tool to a conduit for communion. In addition, as painters apply successive brushstrokes to create depth and texture, I utilise real-time layering to construct images that resonate with the dynamic aspects of nature. Just as layers of pigments, inks and paint brought traditional art to life, my layers of exposures unfold to encapsulate the evolving narrative of the landscapes and my connection to it. This process not only echoes the temporal nature of "shanshui" painting but also invites viewers to witness the passage of time within a single frame. In addition to this another interpretation of layers, pre-dating the Anhui painters the words Jing Hao 荊浩 (ca. 855–915) in Bifaji 筆法記 resonate with me.

According to the Bifaji, there are two layers of reality that should be conveyed in painting to achieve the ideal state of representation, zhen. The first aspect is xing 形—the physical features of an object. The second aspect is the inner quality underlying the visible phenomena of reality, represented as qi 氣 or qiyun 氣韻—the object's character that is to be conveyed in the image (xiang 象) (Powers 1998).

The focus on tactile and haptic qualities in my images finds its parallel in the sensory intent of Anhui painters. These artists emphasised a fresh and untrammelled approach to their work, which was characterized by distinctively dry brushwork, as well as a "boneless" technique where ink washes dominate without the use of clear outlines. These methods give their paintings a sense of fluidity and atmospheric depth. In my use of multiple layers, blurred edges and movement I strive to immerse audiences in a rich visual experience. The rugged texture of a rock, the coolness of a breeze, the whisper of leaves – these tactile details evoke a visceral response akin to the sensory engagement pursued by the "shanshui" painters. By harnessing technology to replicate, or rather be apart of sensory experiences, my images aspire to capture not only the visual but also the emotional essence of the natural world.

The crafting procedure involves the simultaneous overlay of exposures. In contrast to the many Chinese traditional painters, including the Anhui painters my images are completed at the point of capture, rather than making adjustments or edits at the studio or after the event. As the image forms, its multi-layering becomes evident and engaging. The movement and blur originate from the gentle motions of nature and the creator. As one shifts – either deliberately or unintentionally – the image transforms; every breath influences the end result. The individual's physical reaction to the scenery becomes an intrinsic component of the image. As the exhaustion from the hike begins to affect the hand holding the device, and when buffeted by howling winds or freezing rains causing an involuntary shiver, all these responses are captured. They become not only part of the image but also a connection to the moment and nature itself. This sits in contrast to the traditional method of extended photographic exposure is different. Here, the shutter opens to expose the film or digital sensors. Simultaneously, the artist's vision remains hidden until the image is finalised. They can't react to the unfolding image in real-time but can only adjust by reshooting. This process can feel somewhat contrived and indirect.

In the Western world, the relationship between beauty and the sublime has different meanings compared to how it's understood in China. Applying Western ideas about these concepts to Chinese painting is complex as is applying Chinese concepts directly to my making and of course my response to nature, to the sublime, as a westerner. Chinese cultural traditions have shaped beauty and the sublime differently, especially the Sublime. The sense of wonder and awe/fear at nature found in European literature from the 18th to 19th centuries isn't as prominent in Chinese culture. (Fedi 2015)

Chinese aesthetics don't translate directly to Western ways of thinking. Beauty and the sublime in Chinese art follow their own paths, diverging from Western norms. In Chinese painting, these concepts are woven into a distinct cultural story. In China, the sublime isn't just about awe, fear, or trepidation; it's about connecting with nature deeply, and this is a key point of connection with my work. The link between humans and their environment is at the core of Chinese aesthetics. The sublime here is tied to contemplating the universe, the balance of life, and personal experiences. In China, it invites us to go beyond the surface and engage with the bigger questions of existence in an arguably more inclusive way.

Interestingly, as I continue to connect with nature through hiking and the active process of creating my work, along with growing confidence in my interactions with the natural world, I find myself developing a deeper connection and, at the very least, an enhanced understanding of the Chinese conceptualization of the sublime. I should note that is saying a “growing confidence”, this is not an arrogance, nor sense of domination or power , it is more a sense of comfort and belonging. Examining Fan Kuan's painting "Travelers Among Mountains and Streams," I can't help but resonate with Pierfrancesco Fedi's succinct description:

The solemnity and majesty of the mountain is imposing but not threatening. Together

with the energy of the waterfall and the torrent, the mountain towers over and ‘eurythmically’ encircles the tiny figures of the travellers in the composition, which like a cross section of the Universe presents the infinitely small as an integral part of the infinitely large.

Travellers Among Mountains and Streams - Fan Kuan

Travellers Among Mountains and Streams - (detail) - Fan Kuan

https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/travelers-among-mountains-and-streams-fan-kuan/2wGYvjhWju99rw

The presentation of my work as large-scale prints has emerged through a process of experimentation and testing across various sizes. While I previously mentioned that the core of the creative process occurs during capture, it's arguable that decisions regarding scale and printing introduces a level of post-capture creative interpretation. However, it's important to underline that I consciously refrain from making substantial adjustments or edits to the images. Rather, they are rescaled and prepared for printing to ensure optimal resolution and colour accuracy; this comprises the extent of any manipulation.

The final determination of scale is rooted in my pursuit of immersion, proximity to the viewer, and the way I envision viewers engaging with the work. The images are approximately 1 meter wide by 1.8 meters high. This size equates to the size of many scrolls and paintings; however, this was not a conscious consideration in my work. Although some areas of the images may exhibit softness and blurriness, these intentional aspects draw the viewer closer to the surface, inviting them to scrutinize concealed details. Consequently, maintaining resolution becomes paramount to the overall impact of the image. My aspiration is to invoke a dynamic rhythm in the viewer's interaction with the work – an ebb and flow of engagement. As the viewer oscillates between close inspection and stepping back for a broader view, they may discover new points of interest, much akin to my own process of creating the work. This rhythmic dance of exploration mirrors the immersive experience during the act of making, immersing the viewer within the very essence of the image.

The intersection of modern photography and ancient Chinese "shanshui" painting traditions, as explored in my Annapurna Track series, illustrates a profound and dynamic relationship between humans and the environment. Through the use of hand-held devices and a unique layering technique, I've endeavoured to depict not just the tangible landscapes, but also the deeper emotional and philosophical connection I felt during my journey. Drawing inspiration from the Anhui painters and the principles elucidated in the Bifaji, my photographic process attempts to, at least for me as the maker, bridge the gap between Eastern and Western interpretations of beauty, sublimity, and our shared human experience with nature.

In aligning contemporary techniques with traditional ideals, this series serves as a testament to the enduring power of art and nature to facilitate introspection and a deeper understanding of our place in the world. Just as the "shanshui" painters sought to transcend the confines of their canvases, capturing not only the form but the spirit of their subjects, my photographs aim to resonate with viewers on multiple dimensions, from the visual to the emotional. It is my sincere hope that, through this shared journey of exploration and reflection, we may all find renewed inspiration to reconnect with the natural world, appreciating its myriad wonders with a fresh perspective and a deeper sense of gratitude.

Bronek Kozka 2023

Some images from the trip

Powers, Martin J.

1998 “When Is a Landscape Like a Body” In Landscape, Culture, and Power, edited by Yeh Wen-hsin, 1–21. Berkeley: Center for Chinese Studies.

Fedi , Pierfrancesco

Arte dal Mediterraneo al Mar della Cina. Genesi e incontri di scuole e di stili. Scritti in onore di Paola Mortari Vergara Caffarelli, P. Fedi, M. Paolillo (eds.) Officina di Studi Medievali, Palermo, 2015, pp. 535-550.